Miami-Dade Pilots Nation’s First Autonomous Patrol Vehicle to Redefine Community Policing

17 October 2025 | Interaction | By editor@rbnpress.com

Dr. Sean Malinowski of Policing Lab discusses how Miami-Dade’s Police Unmanned Ground (PUG) initiative merges AI, robotics, and public trust to extend the reach of law enforcement.

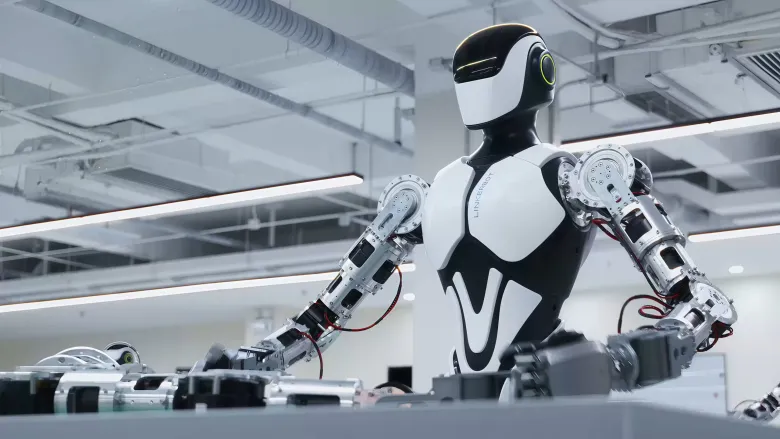

In an interview with Robotics Business News, Sean Malinowski, Ph.D., Managing Partner at Policing Lab, explained the vision behind Miami-Dade’s Police Unmanned Ground (PUG) pilot. “Our goal is not to replace officers but to extend their reach, improve safety, and enhance situational awareness,” he said. Equipped with lidar, radar, 360-degree cameras, thermal imaging, and a tethered drone, PUG operates under human oversight during the pilot, with success measured by safety, community trust, and operational efficiency.

What was the catalyst or strategic driver behind launching the nation’s first autonomous patrol vehicle pilot?

Dr. Malinowski: The catalyst was a combination of rising public safety demands and shrinking human resources. Law enforcement agencies nationwide are facing significant staffing shortages, while communities expect faster response times and more visible patrols. Miami-Dade identified an opportunity to bridge that gap by leveraging autonomy. The strategic driver was not to replace officers, but to extend their reach—giving a single deputy or team the ability to oversee more ground, collect more information, and remain safer in high-risk environments. We saw how drones had transformed aerial surveillance, and we wanted to create a ground-based complement—an autonomous patrol partner that could provide deterrence, situational awareness, and data integration, all while operating nearly 24 hours a day.

Can you describe the key technologies and sensors built into PUG (Police Unmanned Ground) and how they support autonomous policing?

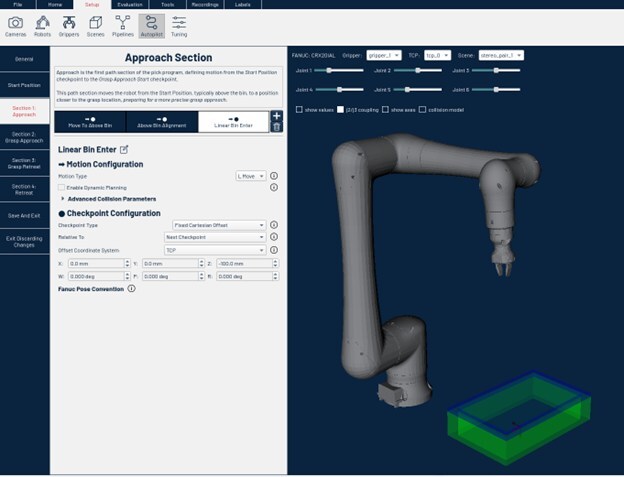

Dr. Malinowski: The PUG is built on a roadworthy platform retrofitted with Perrone Robotics’ TONY autonomous vehicle system. Its sensor stack includes lidar, radar, and a 360-degree high-resolution camera array, each carefully selected to avoid distortion and ensure reliable object detection in urban and suburban settings. A roof-mounted PTZ thermal camera provides long-range detection in low-light or no-light conditions. License plate readers and ALPR software are built in for real-time vehicle identification. A tethered FotoKite drone docking station on the roof allows for rapid aerial deployment when needed, extending the vehicle’s perception beyond line of sight. The drone is optioned with various payloads including thermal and multiple zoom choices. Communication systems include an onboard CPU with 5G connectivity, and an options for Starlink backup for uninterrupted streaming of feeds to the Real Time Crime Center (RTCC). The vehicle will also be equipped with Truleo’s digital assistant technology allowing the operator to query the system on policy, operations protocols and crime information. Together, these technologies create a rolling fusion point—gathering, processing, and transmitting information for both immediate officer use and long-term analysis.

How will you balance autonomous operation vs human oversight during the pilot phase (e.g. having a deputy onboard)?

Dr. Malinowski: Although the vehicle is now capable of full Level 4 SAE autonomous operations, during the pilot, autonomy will be carefully staged. The vehicle will first run in Level 3 autonomy within a geofenced environment, with a trained deputy will remain onboard in the driver’s seat. That deputy’s role will be observation and intervention, not active driving. In order to qualify as an on-board tactical officer, deputies will need to go through a 80-hour autonomous vehicle and technology operations course.

Having a human deputy in the loop ensures two things: first, that the vehicle is rigorously tested under real-world patrol conditions without compromising public safety; and second, that the deputy can act as the human face of the pilot, ready to interact with residents and provide feedback on operational performance. Over time, as confidence grows, we anticipate expanding the role of remote monitoring, where a smaller number of deputies can supervise multiple vehicles from the RTCC, but the pilot will start with a cautious, human-in-the-loop approach.

What are your primary goals and metrics for success in this pilot (safety, community trust, response times, cost savings, etc.)?

Dr. Malinowski: The goals can be summarized in four categories:

- Safety– The vehicle must operate without causing accidents or harm. Metrics include zero collisions, successful obstacle avoidance, and reliable fail-safe behavior.

- Community Trust– We will track public sentiment through surveys, community meetings, and feedback platforms. A key success indicator is whether residents see PUG as an asset.

- Operational Efficiency– Metrics include number of hours of patrol coverage added per week, and quality of situational awareness provided to dispatchers and field units.

- Cost Effectiveness– We will measure cost per patrol hour against traditional staffing, factoring in vehicle acquisition, maintenance, and technology subscription fees. The hypothesis is that PUG will deliver meaningful coverage at a lower marginal hourly cost.

What challenges do you anticipate in public acceptance, privacy concerns, and regulatory compliance?

Dr. Malinowski: We expect three potential challenges.

- Public Acceptance: Some residents may initially fear that an autonomous patrol vehicle feels impersonal or overly “robotic.” Outreach and transparency will be essential—explaining the pilot, showing how it operates, and demonstrating that it augments, not replaces, human officers.

- Privacy Concerns: Anytime a camera or sensor records in public spaces, questions arise about data use, storage, and oversight. We are building clear guardrails: footage will be governed by the same retention and audit policies as other police video systems, and there will be independent command level review of data use.

- Regulatory Compliance: Autonomous vehicles are still governed by evolving state and federal regulations. Working with Florida DOT, NHTSA, and county legal counsel will be critical to ensure compliance with safety standards, insurance requirements, and data reporting obligations.

In what kinds of situations or environments do you expect PUG to perform best, and where might it struggle?

Dr. Malinowski: PUG will perform best in controlled, predictable environments: large shopping centers, business districts, and suburban neighborhoods with wide streets and consistent traffic patterns. These areas allow the autonomy stack to demonstrate reliable route execution and detection. It will also excel at providing persistent deterrence in locations where officer presence is difficult to maintain—such as mall parking lots or industrial zones. Struggles may occur in highly congested downtown streets or during severe weather in unstructured environments. The AV system is able to operate in the rain, but much like a human driver, its visibility in torrential rain can be affected. That is why the pilot will begin in closed route parks and venues and in lower density areas before moving into more varied patrol routes. If the vehicle senses that it’s visibility or sensors or not functional

How will data from PUG integrate with existing law enforcement systems (dispatch, crime databases, surveillance networks)?

Dr. Malinowski: PUG is designed as a node in the larger information ecosystem. Live feeds will flow into the Real Time Crime Center, where they can be overlaid on geo spatial mapping and dashboard platforms. Automatic license plate recognition hits will integrate directly into NCIC and state databases. Incident alerts can be pushed directly to CAD (Computer-Aided Dispatch) and RMS (Records Management Systems), ensuring that PUG isn’t siloed but instead extends the reach of existing tools. The vision is not to create yet another platform, but to make PUG a seamless part of the daily operational workflow.

If the pilot succeeds, how do you envision scaling this across Miami-Dade or other jurisdictions—and what changes would be needed?

Dr. Malinowski: Scaling will depend on three factors: technology, financing, and culture. Technologically, once validated in Miami-Dade, the autonomy and sensor package can be adapted to multiple vehicle types—SUVs, ATVs, or vans—allowing customization for urban, suburban, and border environments. Financially, we envision a Robotics-as-a-Service model, where agencies lease PUG units with bundled maintenance and software subscriptions, making adoption budget-friendly. Culturally, departments will need to evolve training and doctrine, teaching officers how to work alongside autonomous partners. In Miami-Dade, success could lead to deployment in each district, creating a county-wide fleet that provides near-continuous coverage. Beyond Florida, we anticipate interest from large urban departments and federal agencies seeking persistent patrol coverage. Long term, scaling would also mean refining policies on AI decision-making, inter-agency data sharing, and community engagement, ensuring the technology remains aligned with democratic values and local trust.