China at the Helm: SCO Summit 2025 and the Future of Automation, Manufacturing, and Robotics

01 September 2025 | Analysis | By connect@rbnpress.com

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit of 2025, held in Tianjin, has been cast not only as a diplomatic milestone but also as an industrial and technological statement. At a time when the global economy is rebalancing after years of disruption, the Summit is serving as a stage for China to project its growing strength in automation, robotics, and advanced manufacturing.

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

This analysis unpacks the dynamics of the Summit, highlighting how China is positioning itself as the innovation hub of the SCO region, how automation and robotics are shaping diplomatic symbolism, and why this event could be remembered as a turning point in industrial geopolitics.

The Summit as a Platform for Industrial Diplomacy

Traditionally, summits of this magnitude are platforms for policy negotiations, regional cooperation, and declarations of intent. But Tianjin 2025 has gone further—it has transformed into a live showcase of the technologies reshaping industries worldwide.

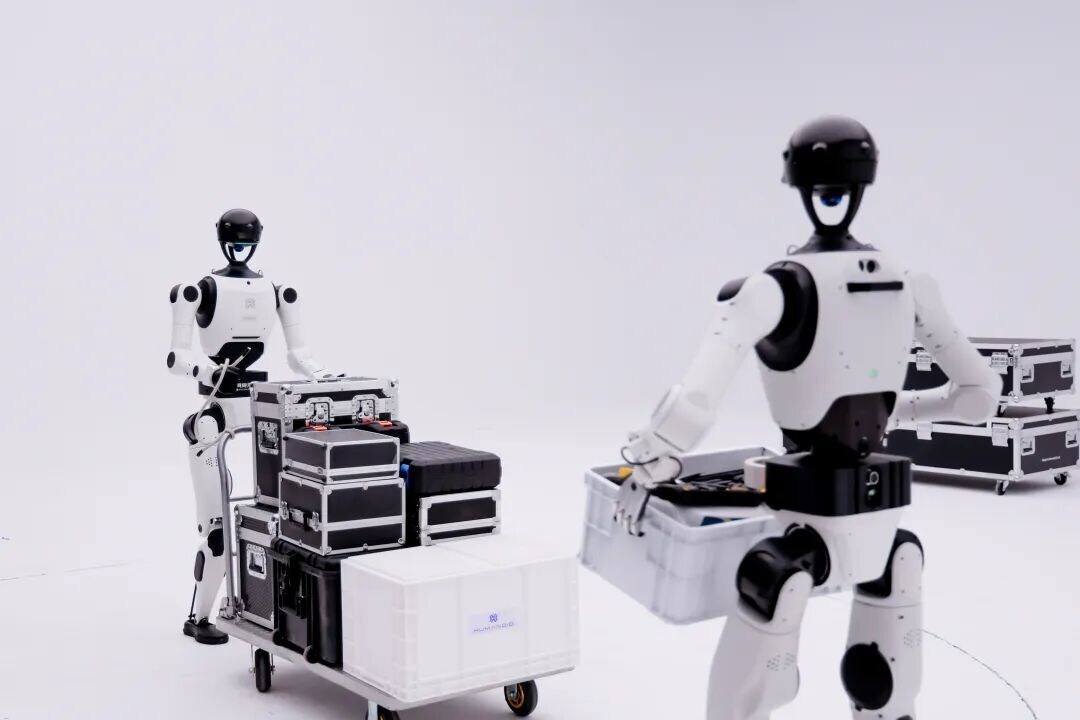

Robots greeting delegates at the venue, AI-driven humanoids interacting with journalists, and smart infrastructure guiding the flow of events all exemplify the convergence of diplomacy and technology. It is no longer enough for states to speak of cooperation; they must demonstrate competence and capacity. China’s choice to embed automation into the Summit environment speaks volumes about its industrial ambitions.

In doing so, China has redefined summitry. The SCO gathering is no longer just a meeting of leaders but an immersive exhibition of what the future of statecraft might look like when powered by robotics, AI, and intelligent systems.

China’s Industrial Blueprint: From Factory Floor to Global Podium

To understand the symbolism of Tianjin 2025, one must look at China’s broader industrial strategy. The “Made in China 2025” policy framework, launched nearly a decade ago, outlined a roadmap for the country to move from being the world’s low-cost factory to a hub of high-end manufacturing. The emphasis was on robotics, semiconductors, aerospace, advanced materials, and next-generation IT.

The results are evident. China now leads globally in the production and deployment of industrial robots. Its domestic adoption has outpaced most regions, and factories powered by automated systems are becoming the norm. In places like Nanjing, robots now manufacture other robots, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of efficiency and innovation.

By aligning the Summit with this trajectory, China signals that its industrial goals are not just about economic competitiveness but also about geopolitical influence. If the world sees China as the unrivalled leader in robotics and manufacturing, then the SCO—and by extension Eurasia—will increasingly orbit around Beijing’s technological gravity.

Automation as a Diplomatic Symbol

Robots at the Summit were not just gimmicks; they were deliberate diplomatic tools. For visiting delegations, being welcomed by humanoid robots underscored two intertwined messages:

-

China’s technological prowess is real and operational—not confined to labs but deployed in real-world environments.

-

The SCO’s future is intertwined with digital transformation—automation is not optional but inevitable.

The humanoid robot “Xiao He,” for example, was showcased as more than a novelty. It represented a merging of artificial intelligence with human-centred service, echoing China’s vision of human-machine collaboration. For diplomats accustomed to protocol, being guided by a robot was both symbolic and disruptive—it forced them to confront the new normal of human-AI coexistence.

By making robotics part of the diplomatic choreography, China turned automation into a shared experience for the entire SCO leadership. It was a subtle yet powerful way of projecting the message: if you want to lead in the future, you must embrace the technologies we are already mastering.

Manufacturing as a Source of Soft Power

Soft power is traditionally discussed in terms of culture, media, or diplomacy. Yet, in Tianjin, China presented manufacturing itself as soft power.

The SCO Summit was framed not just as a political event but also as an industrial exhibition. Agreements signed around sustainable industrial development, smart factories, and advanced infrastructure reflected a blending of economic and political agendas. For China, manufacturing leadership is not just about exports; it is about creating dependency and alignment.

Consider the dynamics: SCO members—ranging from Central Asia to South Asia and beyond—are all at varying stages of industrialisation. Many seek technology transfer, investment, and partnership to modernise their economies. By presenting itself as the hub of automation and robotics, China offers these countries a pathway forward. In doing so, it cultivates influence that goes beyond treaties or aid. It becomes the indispensable partner for industrial growth.

Robotics as the Core of the New Industrial Revolution

The SCO Summit was also framed within the larger narrative of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Robotics, alongside artificial intelligence, is at the centre of this transformation.

China’s leadership in this field is becoming increasingly evident. The country has not only scaled up industrial robots for manufacturing but also expanded into service robots, medical robotics, and humanoid designs. From logistics warehouses to surgical theatres, automation is permeating every sector.

Showcasing these technologies at the Summit was therefore strategic. It communicated to SCO members that China is not only keeping pace with global innovation but is, in many respects, setting the pace. For countries with aspirations of technological modernisation, alignment with China becomes not just beneficial but necessary.

The Economic Dimension: From Investment to Integration

Behind the spectacle of robots and automated systems lies a hard economic agenda. Agreements worth billions were signed in the run-up to the Summit, focusing on areas such as smart manufacturing, infrastructure, and sustainable development.

This economic dimension is vital. The SCO is not merely a political bloc; it is an economic ecosystem with enormous potential. China’s role is to ensure that this ecosystem is built on its technological foundation.

Automation plays a crucial role here. By embedding Chinese systems, standards, and technologies into the industrial upgrading of SCO members, China ensures long-term alignment. The logic is clear: if your factories, robots, and supply chains are powered by Chinese technology, your economic future is inevitably tied to Beijing’s orbit.

Sustainability and Smart Growth

The Tianjin Summit also highlighted sustainability as a central theme. Automation and robotics were presented not just as tools for efficiency but also as enablers of sustainable growth.

Smart factories reduce waste, optimise energy use, and improve productivity. Intelligent logistics systems cut emissions by streamlining transportation. In a world increasingly defined by climate concerns, China positioned its technological leadership as compatible with sustainability goals.

This framing is crucial for winning over both global opinion and regional partners. By linking robotics with sustainability, China moves beyond the stereotype of industrial expansion at environmental cost. It portrays itself as a steward of responsible modernisation—an image that resonates with SCO partners seeking balanced development.

Strategic Implications for the SCO

The integration of automation and robotics into the SCO Summit carries several strategic implications:

-

Redefinition of Cooperation: Industrial cooperation is no longer just about trade or energy; it is about aligning on technological platforms.

-

Standard-Setting Power: By leading in robotics and manufacturing, China can shape technical standards that other SCO members adopt. This creates long-term dependencies and influence.

-

Geopolitical Leverage: Technology partnerships strengthen political alliances. Nations tied to China’s industrial systems are more likely to align with its geopolitical stance.

-

Security Dimensions: Robotics and automation also have dual-use applications, including defence and security. By leading in these areas, China gains leverage in broader strategic matters.

Challenges and Contradictions

While the narrative is compelling, it is not without challenges. Several contradictions accompany China’s push for leadership through automation and manufacturing:

-

Perceptions of Dependence: Some SCO members may welcome Chinese investment but fear becoming overly dependent on Beijing.

-

Technological Gaps: Not all members have the infrastructure to immediately adopt advanced robotics. Bridging these gaps will require sustained investment.

-

Geopolitical Rivalries: Countries like India may view China’s dominance with caution, preferring to develop indigenous alternatives or seek diversification.

-

Labour Concerns: The automation wave inevitably raises questions about employment. For developing economies, this tension between modernisation and job security is acute.

China must navigate these issues carefully if it wishes to translate technological leadership into durable influence.

China’s Dual Strategy: Showcase and Substance

The SCO Summit reflected a dual strategy. On one level, it was about showcasing China’s capabilities—robots greeting delegates, humanoids aiding journalists, AI guiding the flow of the event. This spectacle captured global attention and reshaped perceptions.

On another level, it was about substance. The signing of industrial cooperation agreements, the embedding of Chinese technology into SCO economies, and the policy emphasis on sustainability all ensured that the Summit had tangible outcomes.

This combination of showcase and substance is characteristic of China’s approach to international summits. The spectacle draws attention; the substance ensures alignment.

Towards a New Industrial Order

Looking ahead, the SCO Summit of 2025 may be remembered as a watershed moment in the evolution of international industrial relations. By placing automation and robotics at the heart of the gathering, China has redefined what such summits can achieve.

The world is witnessing the emergence of a new industrial order—one where manufacturing leadership is inseparable from geopolitical influence. For China, this order is not a distant aspiration; it is a present reality being constructed in real time.

Conclusion: Leadership in Motion

The SCO Summit in Tianjin was more than a diplomatic gathering. It was a vision statement, a demonstration of capacity, and a strategic manoeuvre rolled into one.

Automation and robotics were not sideshows but central actors. They symbolised China’s industrial maturity, projected soft power, and cemented economic influence. Manufacturing was not portrayed as a mechanical process but as a strategic resource, capable of binding nations together.

China has positioned itself not just as a participant in the SCO but as its industrial leader. By weaving automation, robotics, and manufacturing into the very fabric of the Summit, it has set the stage for a future in which the SCO is not merely a geopolitical bloc but also a technological ecosystem.

The message from Tianjin is clear: in the industrial geopolitics of the 21st century, leadership belongs to those who master the machines of tomorrow. China is determined to ensure that when history recalls the dawn of this era, it will be remembered as the nation that stood at the helm.